To write this commentary, I draw on my knowledge as historian of twentieth-century Palestinian painting as well as my own experiences with some of these artists when I co-curated Al Jisser Group’s exhibition in New York, “Williamsburg Bridges Palestine.” Additionally, I have a little experience visiting Gaza and communicating with artists there. On one of my visits acting as consultant, I brought the director of the Station Museum in Houston to Gaza as part of the development of the “Made in Palestine” exhibition. This essay will be limited to discussion of static images – painting and photography; but the show is a mix of static pictorial arts, film and video, as well as music.

My first impression of the show and of these artists is their moral good health. It may seem strange that a historian of art would talk about moral health within the parameters of aesthetics. The fact is that art cannot be seen in geographic or disciplinary isolation. And thus as I compare this body of artwork from Gaza to the general aesthetic and moral relevance of much of international production, the sincerity and honesty of Gazan artists appears unusual.

I am moved by their heroism. They continue working and producing art in the midst of destruction and pain imposed by Israeli incursions and encirclement. They overcome depression and adversity and continue to be honest. Several of these artists experienced the anguish of losing not only their homes but also the content of their studios to Israeli bombing. Yet they stand up again and again and continue working. The exhibition titled “Rescue” by Shareef Sarhan, Majed Shala, and Basel El-Maqousi in the wreckage of the Red Crescent Hospital speaks of this more eloquently than words. Is this not the essence of sumoud, that determination to persist that inspired and motivated the previous generation of Liberation artists during the 70s, 80s, and 90s?

The majority of the Gaza artists in this show are educated in the Arab world. A substantial number, perhaps a majority, are educated in Palestinian institutions of art, mostly in Gaza. Some received their art education in Russia. Rare is the individual among them who studied in the West. Some were self-educated. Most of them live and work in Gaza but there are those who live either in the West Bank or in exile. Many are born in refugee camps and say so openly thus taking ownership of the valuable cultural efflorescence in Palestinian camps. But regardless of where they live, Gaza left a strong imprint on their aesthetic consciousness.

One of the marvelous attributes of the show is that it is inclusive. It is refreshingly curated with a very light hand. It does not have that look of the pristine dictatorial museum and gallery exhibition. What it does possess is variety and energy. One sees the accomplished works of artists such as Mohammed Al Hawajri and Tayseer Barakat hanging with works by painters newly graduated from art school. The viewer is given the dignity of deciding for themselves what is important. According to Jasmine Melvin-Kouski, Assistant Curator of the show, Alhoush House of Arab Art and Design uses the technology of the web to “showcase the exciting natural diversity that exists within Arab art.” Moreover, to artists in Gaza, the web has become a precious doorway to the world, an intellectual tunnel through the Israeli cordon.

Gazan artists have taken up the traditions of artistic self-reliance. They have organized exhibitions, galleries, study centers, web pages, and artistic clubs and groups. The studios at the Red Crescent Hospital accompanied by the workshops program and Iltiqa Gallery are examples. They continue the traditions established by the previous generation. It was not an academic historian but rather the wonderful artist, Ismail Shammout, who wrote the first precious book on contemporary Palestinian art during the years of the uprising in Beirut in 1989. It was artists in Beirut and the West Bank and Gaza who organized the Union of Palestinian Artists and the numerous exhibitions of Palestinian art throughout the world and placed it firmly on the international map. Their hard work forms the base for the rich variety of today’s Palestinian arts scene.

The artists of Gaza though living very difficult conditions are nevertheless aware of the world. The currents of art history and of the contemporary art scene are visible in both the form and content of their work. The representation of eyes in the Liberation art of Palestine was used as a symbol to convey that we are aware, we know what is happening to us and we see the world clearly. Interestingly, there are many eyes in the paintings of artists from Gaza. I take note of individual painting with such focus on eyes in pictures by Nariman Farajallah, Dina Matar, May Murad, Majed Shala, Shafiq Radwan, and others. Even in the sad children’s faces in the paintings of Abdelraouf Alajouri the eyes tell of premature awareness. Among the eclectic photographs of the young artist Mahmoud Abu Hamda there is a close up of an eye reflecting the world outside and it seems to share, intentionally or not, the ideas of the liberation artists. Additionally, it presents a principle of internal/external that can apply to situations other than Gaza.

Nowhere, however, are eyes more obviously indicative of knowledge of the world than in the project GAZAWOOD POSTERS, the series of posters by Ahmad Abu Nasser (aka Tarzan), and Mohammad Abu Nasser (aka Arab). These posters indicate awareness of the detailed variances of meaning in international mainstream media’s propagandistic news and of the West’s cultural practices both in film and in postmodernist art.

But there is a difference between the postmodernist works of the Nasser brothers and the exhibition of Gaza paintings. That difference reflects the two trends in Palestinian visual production in our current era. While Palestine remains the primary subject in both trends, they differ in form. One trend, contemporary Palestinian painting, is visual and pictorial relying for its message on visual symbol; the other, Palestinian postmodernist art, participates formally in contemporary international postmodernist trends utilizing interdisciplinary mixed-media and relying primarily on the verbal language. Postmodernist art is not painting; it is a completely different discipline.

The first trend, contemporary Palestinian painting, though comprehensible by the entire world and partly directed towards it, remains inherently aimed at Palestinians and the Arab world. Visible in this work is its descent from the art of the Liberation movement. It relies on it in its formal language even while it differs slightly in content and the use of symbolism. In contrast, the Palestinian postmodernist trend is directed at an international English speaking audient. It utilizes the formal language of postmodernism but subverts its content. It combines static and moving image, and a variety of interdisciplinary media including photography, video, installation, performance, and the spoken and printed word. Like international postmodernism, it relies on communication in the verbal language rather than the visual one. That is not to say that it does not use images; but the images need to be translated to words in order to make sense. Its message does not use the Arabic language native to its practitioners but rather the English language, which has now become internationalized.

However, and what is of primary importance is that the Palestinian postmodernist trend differs inherently from international postmodernism. Its subject matter is sincerely committed to Palestinian aspirations. It does not maintain the elitism and arrogance of subject typical of international postmodernism. In that respect it is a subversive art, an art that borrows contemporary international forms and fills them with Palestinian political aspirations, it takes the forms of oppression and fills them with the content of the oppressed. The Nasser brothers do this with unmatched bravado as though to say we understand how you imprison us so take a look at how well we understand your prison. Thus in GAZAWOOD the prominent eyes are indicative of intelligence, humor, and international awareness.

Not included in this show but notable as another Gazan postmodernist work is the “Gaza Metro” by Mohammed Abusal. Abusal photographs a metro sign in various parts of Gaza, thereby fulfilling a wish while making a poignant comment about the abnormality of life in Gaza. It tells an international audience, that look your life is not like ours; while being sarcastic and painfully humorous.

Contemporary Palestinian painting practiced by a majority of the Gazan artists is a continuation of earlier traditions. Visible are not only the formal influences of the previous Palestinian generation of painters but also that of historic Arabic art as well as the ancient arts of the region. The remainder of this essay deals with contemporary Palestinian painting and photography as static single images first as to its form and lastly as to its content.

Unlike the Liberation artists, the painters of Gaza tend to be more expressionist than symbolist. The influence of expressionism in their work came directly through the agency of Darat al Funun in Amman where for a time German-based Syrian artist Marwan Kassab Bachi would teach in their summer program and where its good director, Suha Shoman, made certain that many artists from Gaza came to study. In Marwan’s paintings, faces form a major subject and are distinguished by marvelous brushing. After the first wave of students returned to Gaza, faces as well as free brushing began to dramatically appear in their paintings. They are used to good effect in the paintings of Shafiq Radwan, where faces of various scale fit next to one another or inside each other all looking out at us in their various attitudes. The wonderful brushing of Marwan affects Abdel Nasser Amer, Ruqaia Al Lulu, and Mohammed Harb (who uses broad brushing to paint expressively distorted faces and figures in bright colors).

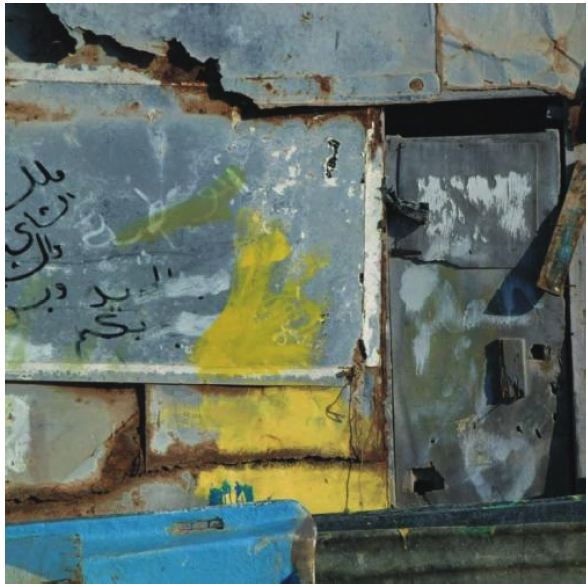

Another formal tendency which appeared in the art of liberation artists and which has its origins of medieval Arabic (Islamic) geometric abstraction is the tendency to fit shapes tightly together so as to fill the flat space of the picture’s plane. The clearest use of this is to be found in the work of Rima Al Mozayyen, who fills the picture with flattened shapes so fitted as to fill the picture’s surface. The photographs of Majed Shala also reveal the innate aesthetics of medieval Arabic (Islamic) art in the way the parts relate to one another though the subject is contemporary. Shala focuses his lens on small intimate sections of camp architecture where surfaces reveal that they are old, used, and disparate. They reveal the camp builders by expressing the poverty and artistry of their hands. Furthermore, bits of graffiti reveal the disenfranchisement of the residents as they have only their own walls to express their political and religious ideologies. Some of the photographs of Khalil Al Mozayen might also be included in this discussion where the texture of Gaza architecture is a central subject revealing the effects of destruction and use. Mozayen is a highly trained and experienced photographer. Salman Nawati, Shadi Alassar, Basel El-Maqousi, and Omar Shala all present very capable photographs.

[Majed Shala. Image copyright the artist.]

[Majed Shala. Image copyright the artist.]

The influence of the ancient arts of the region are visible in the work of Tayseer Barakat, where rows of images are knowledgeably influenced by ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, and Sumerian arts. In Barakat’s work, images in rows and compartments tell about the small compartments of life in refugee camps. The paintings of Raed Issa present figures that appear to be youths struggling against attacking Israeli soldiers. While this painting represents life in Gaza, it is formally aware of the relationship of negative to positive space so clearly visible in the work of Mustafa Hallaj and in Arabic geometric abstraction as well as Arabic calligraphy and the ancient arts of the region.

Whereas the formal attributes of contemporary Palestinian painting owe much to the past, as they should, its subject matter reflects contemporary life in Gaza. The untitled painting in the show by Nariman Farajallah presents rows of figures, bandaged, wrapped, swirling, bent, hung, or buried by debris. The paintings of Abdelraouf Alajouri bring us the children of Gaza and the frightened child in every adult. We can read the psychological weight forced on to the hearts of the people of Gaza in these children, naked and fragile. The figures in the paintings of Iyad Sabbah combine the contradictory sensations of refuge and torture. The painfulness of life in Gaza is also clear in the figures painted by Mohammed Joha, which are made to look like damaged mannequins. There is not blood, yet we are affected by figures that are crucified, upside-down, and bandaged. The photographs of Nidaa Badwan belong in this group of works that express the anguish of life in Gaza. Nidaa uses a combination of facial expression with a black plastic bag tied around the head implying suffocation and garbage. These artists have all found ways to express their observations of anguish in Gaza making the visual expression far more powerful than words.

[Nidaa Badwan, untitled. Image copyright the artist.]

[Nidaa Badwan, untitled. Image copyright the artist.]

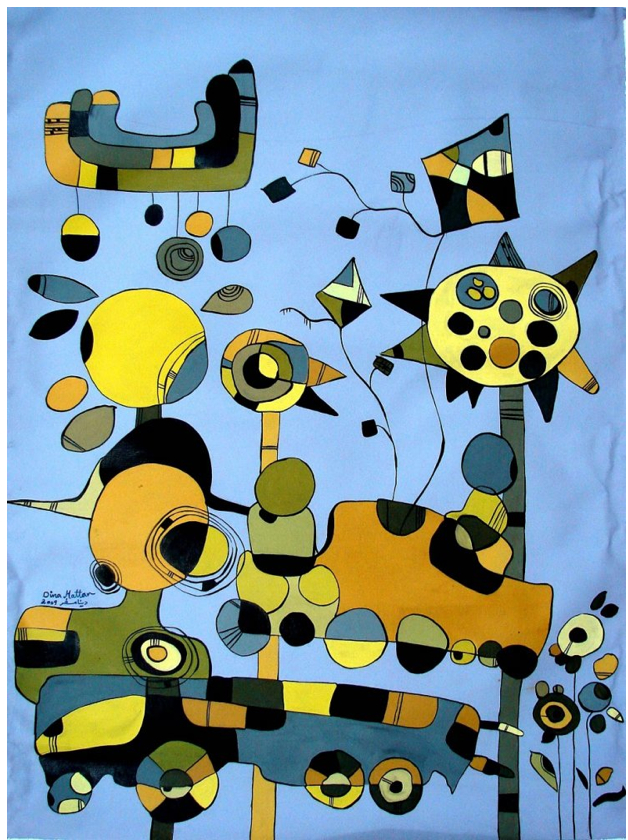

In subject matter, the work of Dina Mattar brings the paintings of Ahmad Nawash to mind. Like Nawash, Mattar’s pictorial organization is superb. Kites, birds, figures, and other objects in her paintings posses a certain humor and delight; but they also posses a clearly compelling structure that is neither informal nor carelessly invented. The viewer begins to decipher what seems an intentional story and begins to question what is happening between the personages in the paintings. That is the precise attribute that brings Ahmad Nawash to mind. It could very well be a similarity of life and experience or a direct influence, it makes no difference as visual culture has a way of permeating our consciousness in ways that we are hardly aware of. What I find of interest is that her paintings also bring the Spanish painter Joan Miro to mind, but though the resemblance to Miro is outwardly close it is far weaker than the compelling similarity of attitude to the work of the old master, Ahmad Nawash.

[Dina Mattar, untitled (2009). Image copyright the artist.]

[Dina Mattar, untitled (2009). Image copyright the artist.]

The visual work presented by this exhibition deserves very careful consideration and respect. It carves out a space in the world of Art that is unique. Though the artists of Gaza live in a painful prison, they are surrounded by subject matter fit for epic poetry, and they manage to find the sincerity and the willpower to standup and to use it. They manage to stand up not only against the painful odds of a difficult life but they also stand up in spite of the overwhelming propaganda of oppression designed to make them feel inferior. This contrasts starkly to comfortable societies where artists are unable to withstand the temptations of elitist propaganda designed to make them feel superior and produce visual works that are vacuous. The artists of Gaza are indeed heroic.

This essay first appeared in the THIS IS also GAZA exhibition catalogue that was published on the occassion of Alhoush House of Arab Art and Design`s inaugural event and is reprinted with permission of the author.